He refers repeatedly to “the journey,” his boxing career which began in the waning days of the Reagan Administration as a part-time fighter who awakened at 4:30 in the morning not to do road work but to prepare to go to work to support himself because there was no hint in October 1988 that Bernard Humphrey Hopkins would make anything of himself as a boxer.

There was no reason to believe that 28 years later, he’d be preparing to fight a man 24 years his junior, with millions in his bank account, his Hall of Fame ticket punched, the legacy that he speaks of so often secure.

On Saturday, a little less than a month before he turns 52, Hopkins fights for the 67th and final time when he faces 27-year-old Joe Smith Jr. on HBO at The Forum in Inglewood, Calif., in what he says he hopes will be a “time of celebration, not sadness.”

For the last decade-and-a-half, maybe more, Bernard Hopkins has freely, and frequently, discussed his legacy.

As he was in the process of reeling off 20 consecutive successful defenses of his middleweight championship, he seemed more concerned with explaining the historic nature of his streak to boxing writers who weren’t openly celebrating him than he was with the skills of a man who was about to try to knock him senseless.

He’d made it from the depths, surviving a five-year prison stint on a strong-arm robbery conviction, turning his life around to become part of the establishment he once so despised.

The guy who battled and sued promoters almost as regularly as he boxed is now a promoter himself. The man whose skill helped him to become a millionaire many times over still holds a Costco card, buying in bulk to save a few bucks.

The man who once stomped on a Puerto Rican flag and had to be hustled into the safety of a dressing room in Roberto Clemente Coliseum in San Juan as enraged Puerto Ricans attempted to break down the door, now says his life is the quintessential All-American story.

There is a made-up belt on the line for the final act, but the bout against Smith is not about championships or rankings. Rather, it’s about an extraordinary athlete with the kind of discipline and self-control few have ever possessed doing the seemingly impossible one more time.

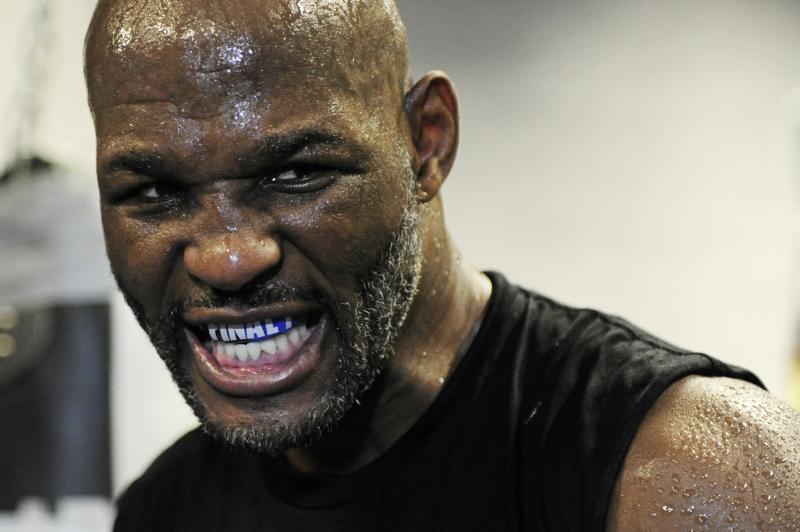

He’s defied the laws of aging, and boasts “I’ve got the body of a 25-year-old.”

He’ll be remembered for his lengthy streak of successful middleweight title defenses, from defense one against Steve Frank on Jan. 27, 1996, through defense No. 20 as a 40-year-old on Feb. 19, 2005, he dominated the middleweight division as few others have.

Were there better middleweights? Undoubtedly. Sugar Ray Robinson, the greatest pound-for-pound fighter of all-time, had a lengthy stint at middleweight. And others, like Harry Greb, Carlos Monzon and Marvelous Marvin Hagler, are generally rated above him by boxing historians.

The list, though, is short, and Hopkins’ accomplishments are long. He’s known best, perhaps, for his stunning takedown of heavily favored Felix Trinidad in the finale of Don King’s middleweight tournament that came in the highly charged, emotional atmosphere just two weeks after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

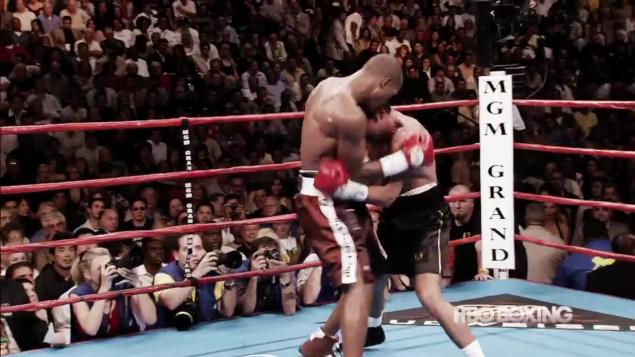

Perhaps the first indication to the world of his greatness, though, was his March 16, 1996, middleweight title defense against unbeaten Joe Lipsey in Las Vegas.

The fight was shown on ABC’s “Wide World of Sports” hours before Mike Tyson would defend his heavyweight title against Frank Bruno later that night in the same arena.

Hopkins was largely ignored as the media descended upon Las Vegas to track Tyson’s every move.

Ex-football star Dan Dierdorf and Alex Wallau, the president of ABC, called the fight. Dierdorf said in introducing the bout to his audience, “In this era of boxing, we see a lot of fights which just aren’t competitive. Lo and behold, we have the No. 1 contender fighting the champion and this bout is just about a toss-up.”

Hopkins had won the belt less than a year earlier, when on the second try following an initial draw, he stopped Segundo Mercardo to claim the IBF crown.

Lipsey was 25-0 with 20 knockouts, and though he didn’t have great opposition, there were many at the time who expected him to defeat Hopkins.

“The unbeaten challenger, Joe Lipsey, has a lot going for him,” Wallau told the television viewers. “He’s got quick hands, good power and a difficult southpaw style.”

The first two rounds were close, and Lipsey had his moments, though Hopkins won them on all three cards. In the third, Hopkins began to assert himself, scoring with heavy shots as Lipsey began to wilt.

And then, as the fourth round was coming to a close, Hopkins landed a vicious right uppercut. Lipsey froze, seemingly out on his feet. Hopkins followed with a blistering straight right hand, a left hook and several more rights.

Lipsey went down on his back and the fight was stopped without a count.

More than 20 years later, upon hearing Lipsey’s name, Hopkins slowly repeated it. It is one of his most glorious, and significant wins, though it’s rarely spoken about.

“Ah, Joe Lipsey,” Hopkins said, drawing out the final syllable of Lipsey’s last name. “Great fighter. He could punch, man. Real good puncher. The guy could punch. Good fighter.”

He seemed, for a brief moment, to wander back to 1996, reveling in the dominance of his win. When it was noted that Lipsey never fought again after losing to him, Hopkins jolted back into the moment.

“He’s not the only one,” Hopkins said. “Joe Lipsey was never the same. Felix Trinidad was never the same. Jermain Taylor. There were a lot of them.”

He says this because he knows there’s been a large segment of the media and the fan base who have derided him as boring, as a safety-first fighter not willing to engage.

But he must have done something offensively to so alter those fighters he’d beaten, he’ll argue.

“You know, maybe the way Bernard Hopkins fought was boring to a lot, but just think of this,” he says. “If I fought the way people wanted me to fight, I wouldn’t be in a car right now in Manhattan heading to HBO, talking to you, going over all my achievements. And you know, for years they said Bernard Hopkins was not an exciting fighter and more of a defensive fighter and this and that.

“It was the best thing I’ve ever done, to stick to what I believe in and stick to what I’ve been taught: Hit and not get hit, deflate the balloon and take advantage of my opportunities.”

For all of his wins, for his numerous amazing accomplishments, he freely admits he was still treading uphill against the grain when he fought Oscar De La Hoya for the undisputed middleweight title in 2004.

“That fight with Oscar not only brought me to Jay Leno’s couch that [following] Monday, but that was the fight, not the Trinidad fight, which made me a superstar,” he said. “I thought it would be the Trinidad fight that made me a superstar, but I’m not being cliché here when I tell you that without the Oscar fight, I wouldn’t be a superstar and I wouldn’t be in partnership with the best promotional company in the sport and I wouldn’t have this opportunity in front of me.”

He became the oldest man ever to win a major title in 2011 when he defeated Jean Pascal in Montreal, doing push-ups between rounds to send a message that his age on the calendar was meaningless.

He set a mark that may never be broken on April 19, 2014, when he defeated Beibut Shumenov for the light heavyweight title at 49 years, 3 months and 4 days old, to become the oldest man to win a world championship bout.

And now, on Saturday, he hits the stretch run of his career, headed for home while fighting a man who wasn’t born when he made his professional debut.

Hopkins is closer in age to the legendary Muhammad Ali, who died in June at 74, than he is to Smith.

It’s remarkable, and he’ll bask in the accolades and the cheers from the crowd that will undoubtedly rain down upon him when he makes the long, slow walk to the ring for the last time.

But that’s not what he’ll miss so much about a fight career that spanned nearly three decades. It’s not the title belts or the glory or being the center of attention.

“What I’ll miss about being an active fighter won’t be about the actual fight itself,” he said. “What’s going to be hard to get over is not getting them big checks after the fight is over with. That will be hard, believe me. It’s always been nice seeing them big checks.”

The big checks came because he honored his sport. He never came unprepared, never gave less than his best and was never caught looking ahead.

Win or lose, he’ll leave the ring not only a millionaire, but also confined to the history books as one of the greats not just of his time, but of all-time.

More News

Liu Gang, Brico Santig Join Forces

Highland’s Double Impact: August 18 at Lumpinee

Balajadia, Atencio in Action in Thailand