Bloodyelbow.com

Co-authored with David Christian of The Modern Martial Artist

During the first decade of MMA, the preferred striking style appeared to favor the Muay Thai practitioner. Perhaps it was because pioneers like Marco Ruas and Pedro Rizzo were so effective with it. Or it might be the early application of other striking arts like boxing (e.g. Art Jimmerson in UFC 1) failed given the singular repertoires of that time. But times have changed, and striking styles one time thought null and void in MMA are proving to be tactically effective.

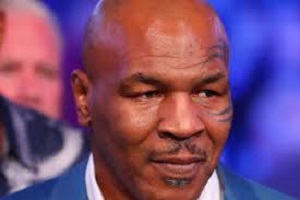

Cus D’Amato, the genius coach of Mike Tyson, may have engineered one of the most brilliant styles ever witnessed in boxing, the peek-a-boo style. Rooted in what D’Amato called elusive aggressive, he taught his fighters to move their head to avoid punches, and to use this head movement to set up punches with bad intentions. While many fighters perceive an incoming strike as a threat, Tyson and other D’Aamato protégés approached the opponent’s offense as an opportunity to unleash devastating offense. As a result, many opponents began throwing punches primarily as a defensive tool intended to keep Tyson at a safe distance. Because of his head movement and lunging foot work aimed at closing distance quickly, these defensive strikes further played to the strengths of Tyson’s peek-a-boo style.

Using a squared stance and tight guard with palms turned in, Tyson’s style was very nuanced and atypical. Though his style as a whole was best fit for the shorter fighter in boxing, there are many elements of the peek-a-boo style that can be applied tactically in MMA. Below and in the follow-up article we explain some key elements of Tyson’s style so the reader might consider how a few of these might be employed effectively in MMA.

Head Movement

Many perceived Tyson’s biggest attribute as being his punching power. While this certainly was important, it was not at the root of Tyson’s success. Defense was. Specifically, defense anchored in head movement. One of the strengths of Tyson’s movement was that he would slip so deep to his jab side that he could literally avoid straight punches, hooks, and uppercuts with this singular movement. Like a deep keel intended to keep a sailboat from tipping, Tyson used a strong base and core to “tilt” his upper body like a sailboat in strong winds. This effectively removed his head as a target but kept him in position to deliver a wide range of punches.

Another strength of Tyson’s head movement was that it was built in to his striking. In other words, strikes, particularly the jab and the two, were thrown with the head “off-line.” This allowed him to generate greater velocity to maximize power, while simultaneously incorporating defense as he struck his opponents.

A good example of this was Tyson’s use of the “slip-jab.” Tyson would use this as an entry punch to safely slip to the outside of a longer opponents jab as he simultaneously jabbed with his head off line. Once inside he was able deliver a powerful straight or overhand two.

Another tactical use of head movement was the “jab-slip.” Using this entry punch, Tyson would power forward with a jab, immediately slip to his left to avoid the counter, and then “counter the counter” with a ferocious hook set up by simultaneous opening of his hips and bending of his knees to allow him recoil like a snake.

Finally, where the common approach to slipping a jab is to move the head outside the opponent’s jab then counter with the two (as Tyson did with his slip-jab), Tyson would also slip deeply inside the jab then counter with his hook.

While head movement in MMA can be risky because of kicks and knees, tactically applied it can be used to overcome reach advantages and close distance to either attempt a strike or takedown. Where Tyson’s head movement was extreme, in MMA head movement should be “just enough” to avoid incoming punches and mitigate the risks associated with kicks and knees.

Power

In physics, Power=Force x Velocity. To break that formula down further, Force = Mass x Acceleration. Simply put, the bigger a fighter is, and faster he accelerates his punches, the greater the force behind it. And Velocity=Distance/Time. In other words, punches that cover a greater distance in a shorter amount of time have greater velocity. So when you put it all together, the bigger the fighter, the quicker the acceleration, and the faster the punch covers distance, the more powerful the fighter.

While scientists have labored for decades to better understand and determine predictors of power in combat sports (e.g Loturco, Irineu, et al. (2016), Tyson seemed to own these laws of physics. Whether he used the jab-slip, rolled, or simply slipped inside or outside of an incoming strike, Tyson always used his defense to maximize power by loading his punches. He frequently did this by turning his hips, tilting his torso, and engaging in a slight squat to prepare for an explosive strike, typically a hook or uppercut. Some of the keys to his power included:

- Maximizing velocity by ensuring full hip/torso rotation

- Allowing his rear foot to “pivot” to minimize friction and allow for full hip and torso

- Increasing force by exploding (accelerating) into his strike. Like a pendulum held high then released to swing high in the other direction, Tyson’s explosive force paired with velocity increasing core rotation resulted in his next punch being fully loaded so he could maintain power with each punch.

- Akin to swinging a wrecking ball, Tyson would relax his momentarily relax his arm when striking to prevent muscles from “fighting” other muscles which creates fatigue and reduces speed.

- Following a simple strength and conditioning program (e.g. squats, medicine ball exercises) that strengthened key muscles associated with rotational power (Krantz, 2007)

Timing

A quick review of non-scientific sports articles reveals that timing is a rather ambiguous and diverse concept. While recognized by coaches and fighters as an important factor for successful performance in combat sports, there is little consensus to what it is. Timing, or the “temporal coordination of parallel activities or actions” (Nationalencyklopedins ordbok, 2000) as it has been defined in certain literature, was a critical piece of Tyson’s style. Timing, as referenced in sports journals, includes skills in “observing, controlling and differentiating the rhythm of a specific motor action, depending on the situational demands” (Martin, 1988). Simply put, timing is doing the right thing at precisely the right moment.

Tyson was very skilled with either moving his head as soon as he was provided even the slightest indication his opponent was striking, or actually striking simultaneously with his opponent with his head off line. Like a baseball player who begins his swing only milliseconds after the ball has left the pitcher’s hand, Tyson learned to begin his movement quickly based on precursors to his opponents strike. For example, the slightest hand movement, shoulder movement, hip movement, or combination of movements would evoke an immediate and perfectly timed response from Tyson.

FOOTWORK

The Shift

Tyson was highly adept at shifting, but not in the way that pertains to most fighters. Usually, a fighter will change stances by stepping forward in order to chase their opponent. Tyson surely did a lot of that himself, and MMA fighters use similar shifting techniques in conjunction with kicks and takedowns. But Tyson also used more subtle, advanced footwork to reposition himself into superior angles from which to attack. This shifting style capitalized on the fact that Tyson had knockout power in either hand and was completely comfortable in either an orthodox or a southpaw stance.

As mentioned before, Tyson tended to enter deep into his opponents space, usually placing his rear foot near his opponents lead. This left Tyson’s feet nearly parallel with his opponents, with both men in neither an orthodox nor a southpaw stance. Instead, they now fought facing each other in a nearly neutral stance. Tyson was entirely comfortable fighting from this extremely dangerous and open position, while his opponents usually were not, to say the least.

But the true brilliance of this parallel position was that Tyson could easily transition into any stance or any angle he chose. And Tyson was highly adept at picking the perfect position from which to attack.

To give an example of Tyson’s incredible ring IQ, we can take a closer look at his foot positioning when transitioning into southpaw from the parallel position. It’s fairly well known that placing your lead foot on the outside of your opponents lead foot creates a “dominant” position when fighting from southpaw. The position shortens the distance from your rear hand to your opponent’s centerline, and provides some additional protection from their power hand as well.

And as such, Tyson did use this position when throwing with his rear hand, especially when chasing a retreating opponent. But when he transitioned into southpaw to throw one of his devastating lead uppercuts, he would instead keep his lead foot on the inside of his opponents. Why? Because in the same way that an outside foot position provides a better angle to land your rear hand, an inside foot position provides a better angle for landing with your lead hand. Tyson would shuffle into this uppercut to corner his competitor, and step back into southpaw to create space.

These are only a few examples of Tyson’s seamlessly brilliant footwork, are explored in the video here:

In modern day MMA, a few high level fighters have pulled off these transitions in different ways.Max Holloway is a great example of a fighter who gets deep into his opponent’s stance, even shifting forward or using oblique kicks to enter; T.J. Dillashaw has had great success using Tyson like shifting to change to new superior angles; and Demetrious Johnson has mastered his own modified version of the D’Amato Shift

The D’Amato Shift In MMA

A D’Amato shift is when a fighter enters so deep into his opponent’s guard that both fighters end up changing stances. In other words, both fighters enter an exchange in an orthodox stance, and one fighter moves so far forward that they both end up facing each other in a southpaw stance.

This technique is highly beneficial to multi-stanced fighters who look to take advantage of the awkwardness that single-stanced fighters feel when fighting in their non-dominant stance.

However, the downside is that this move leaves you ridiculously open as you move past your opponent to leave out the other side. This holds even more true in MMA than in boxing. But Demetrious Johnson has come up with his own unique way to use the D’Amato shift.

Mighty Mouse is still able to capitalize on this advanced footwork to set up shots and escape corners. He does this by clinching as he shifts, controlling his opponent’s posture and guard as he changes positions. A typical Mighty Mouse exchange using a D’Amato shift might look like so: Enter with a cross, secure a wrist lock and collar tie to avoid counters, shuffle past your opponent to change into a southpaw stance, and then exit off of a jab.

The conclusion is that Tyson’s advanced footwork is applicable to MMA, but only if grappling and wrestling techniques are implemented at the same time. The low, crouching head movement can be used to feint or set up for takedowns, and clinching can be used to remain safe while changing angles.

Though simple in purpose, Tyson’s style was very complex and can easily be studied and explained through a variety of theoretical approaches, including, but not limited to neuroscience, Applied Behavior Analysis, physics, and psychology. Not intended to cover every aspect of Tyson’s style, we hope this article shed light on a couple of the key elements that might be used tactically in MMA. If you want to learn some simple strategies for increasing your fluency and effectiveness with head movement, stay tuned for the second part of this article titled Fight Science: How to move your head like Tyson.

References

Krantz, J. (2007) Rotational power training: the foundation for all athletic power. Brian Mackenzie’s Successful Coaching,(ISSN 1745-7513/ 39/ February), p. 5-8

Loturco, Irineu, et al. (2016). Strength and Power Qualities Are Highly Associated With Punching Impact in Elite Amateur Boxers. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 30(1), 109-116.

Martin, D. (1988). Training im kinders – und jugendalter. Verlag K. Hofmann

Nationalencyklopedins ordbok. (2000). Nationalencyklopedins ordbok [Dictonary of the Swedish National Encyklopedia]. Höganäs, Sweden: Bra Böcker.

Bios

An expert in leadership and human performance, Dr. Paul “Paulie Gloves” Gavoni is a highly successful professional striking coach in mixed martial arts. As an athletic leader and former golden gloves heavyweight champion of Florida, Coach Paulie successfully applies the science of human behavior to coach multiple fighters to championship titles at varying levels worldwide.With many successful fighters on his resume, Coach Paulie tailors his approach to fit the needs of specific fighters based on a fighter’s behavioral, physiological, and psychological characteristics. Coach Paulie is a featured coach in the book, Beast: Blood, Struggle, and Dreams at the Heart of Mixed Martial Arts and the featured Bloody Elbow article Ring to Cage: How four former boxers help mold MMA’s finest. He can be reached atpauliegloves@gmail.com.

More News

Casimero TKO’s Sanchez in 1st round

Raquinel wins WBC Continental Americas super flyweight title

Frank vs Raquinel on ABEMA LIVE PPV