boxing.com

The New York Times wrote that “during his long retirement, [Dempsey] set a standard of dignity rarely equaled by a former champion…”

Former heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey has always been a subject of great fascination to me. His aggressive style and tremendous punching power and humility made him a cultural icon of the 1920s.

Born William Harrison Dempsey in Manassa, Colorado, in 1895, the future champion grew up dirt poor and left the family home as a teenager. He rode the rails, hopping freights and bunking down in mining and homeless encampments throughout the American West.

He soon began boxing in saloons and labor camps under the names Kid Blackie and Young Dempsey, often beating full grown men. In 1918 he fought 21 times, defeating such established boxers as Gunboat Smith, Battling Levinsky, Bill Brennan and Billy Miske.

On July 4, 1919, the Dempsey legend was born after he stopped the gargantuan Jess Willard in the third round. At 6’1” tall and 187 pounds, Dempsey was dwarfed by Willard, who was 5½ inches taller and 58 pounds heavier.

After knocking Willard down seven times, the former champion, who previously had never been off his feet, described Dempsey as “a remarkable hitter.”

Dempsey won five bouts, including a savage brawl against Luis Angel Firpo, before meeting Gene Tunney in September 1926. Tunney, a former Marine, would win a unanimous decision in Philadelphia in front of more than 120,000 fans.

Dempsey later told his wife, “Honey, I forgot to duck,” when explaining the inexplicable loss. That same line was repeated by U.S. President Ronald Reagan more than a half-century later when he was shot and wounded by would-be assassin John Hinckley in 1981.

Dempsey rebounded from the Tunney loss with a stoppage win over future titlist Jack Sharkey and then faced Tunney in a rematch in September 1927 in Chicago. In that fight, which is known as “The Long Count,” Dempsey again lost a decision to the extremely clever Tunney.

The losses to Tunney did not diminish Dempsey’s widespread popularity in any way. After retiring with a final ring tally of 54-6-9 (44 KOs), he dabbled in Hollywood and opened Jack Dempsey’s restaurant in New York in 1935.

The eatery and bar was located on Eighth Avenue and West 50th Street, directly across from the old Madison Square Garden.

The restaurant’s name was later changed to Jack Dempsey’s Broadway Restaurant when it relocated to Broadway, between West 49th and 50th Streets. It was there that he held court daily, greeting visitors with his standard “Hiya, Pal,” until a rent dispute forced him to heartbreakingly close its doors in 1974.

What made Dempsey so interesting to me was the fact that during many visits to the International Boxing Hall of Fame in Canastota, New York, in the 1990s, so many older men, all of whom were 60 or more, described Dempsey as their childhood hero and spoke of him in such reverential terms.

Many of these men, including the late Bob Shepard, a longtime boxing collector and appraiser for Sotheby’s, seemed awestruck when discussing Dempsey with his contemporaries. Shepard even owned a sports jacket that had been custom-made for Dempsey and had the name of the tailor and the champ sewn inside.

A few months ago I visited Dempsey’s grave in Southampton, New York. I always get nostalgic at cemeteries so my imagination began to wander. I was forlorn that I never got to meet the great Dempsey, nor did I ever visit his restaurant.

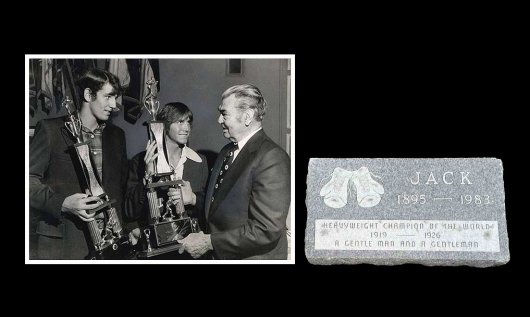

I recalled a photo that appeared in the New York Daily News in the early 1970s, when Dempsey congratulated teenaged boxers Gerry Cooney and “Irish” Johnny Turner for their outstanding performances in the city’s Golden Gloves tournament.

He presented them with giant trophies and praised them for their fistic acumen.

“Meeting him was like meeting Babe Ruth,” said Turner. “I had read a lot about him, and I was in awe of him.”

Between 1975 and 1984, Turner, now 62, compiled a professional record of 42-6-2 (32 KOs). He also appeared in the Academy Award winning film “Raging Bull.”

Cooney, who will turn 61 later this month, challenged Larry Holmes for the heavyweight title in 1982 and retired eight years later with a record of 28-3 (24 KOs).

He recalls the experience of meeting Dempsey as “pretty exciting.”

“He was an awesome man and champion, but I was too young to recognize his greatness,” said Cooney. “He told me I was big and tall and would have a nice career if I worked hard. He was kind of quiet, not very outspoken, but there was something about him that stood out.”

When Dempsey passed away from a heart ailment at the age of 87 in 1983, the New York Times wrote that “during his long retirement, [he] set a standard of dignity rarely equaled by a former champion.”

Cooney and Turner, both long retired, now in their sixties, in good health and living fulfilling and enriching lives, could not agree more.

More News

IBF Asia Heavyweight Title Fight: Bisutti vs. Nattapong

Liu Gang, Brico Santig Join Forces

Highland’s Double Impact: August 18 at Lumpinee