For the longest time, Larry Holmes was underappreciated. A poor man’s Muhammad Ali they said. Not an authentic knockout puncher. Lacking in charisma. It didn’t matter what “The Easton Assassin” accomplished, it was never good enough.

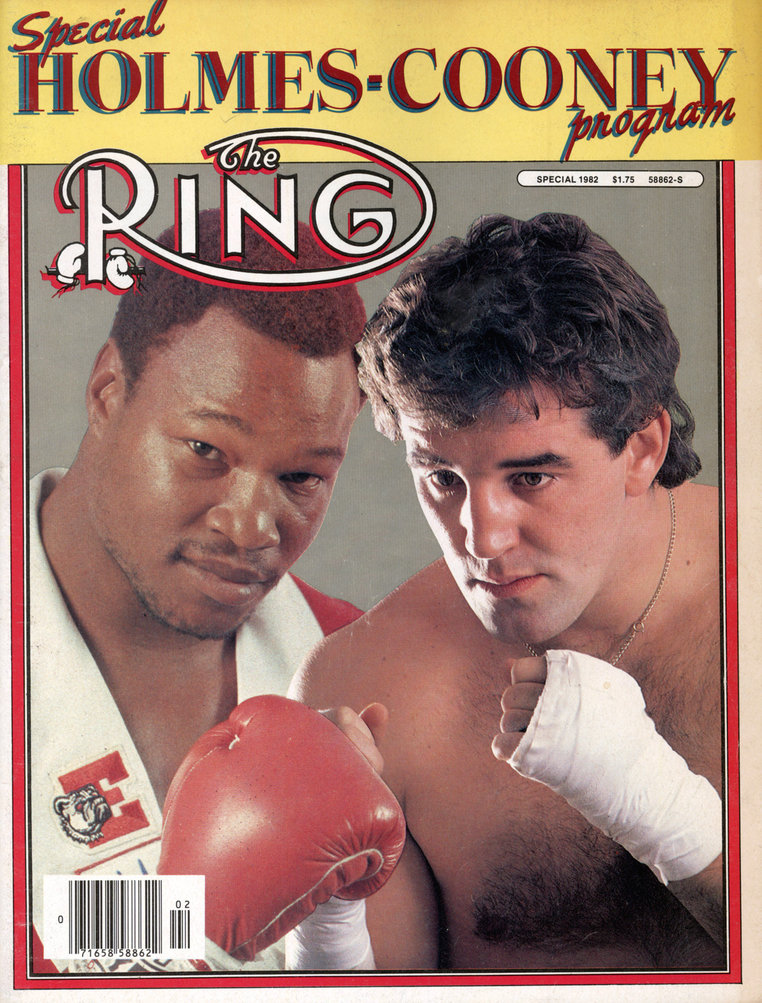

That was the theme in what was arguably Holmes’ most defining heavyweight title defense. On June 11, 1982, Gerry Cooney was 25-0 (22 knockouts) when he challenged Holmes for THE RING and WBC titles at Caesars Palace in Las Vegas. It was the most eagerly anticipated heavyweight title showdown since Ali’s glory years – and it delivered. Holmes, who mixed tactical superiority with well-timed aggression, impressively retained his championship via 13th-round stoppage and Cooney fought the fight of his life in a gallant losing effort. It was a sporting moment to be celebrated but instead, Holmes-Cooney is remembered for all the wrong reasons.

“Gerry was much better than I thought he was and I tell him that to this day,” Holmes told RingTV.com. “When he fought Kenny Norton, I didn’t think he was going to win that fight but he took Kenny out in a few seconds (54). The problem was that a lot of people didn’t give him credit. They gave him credit before me but after I beat him, they said Gerry Cooney wasn’t nuthin’. But he was a helluva fighter.

“He didn’t get himself back (to world title contention) but fighting me, and losing to me, took a lot out of him. That was the sad thing about it. If Gerry fought someone else, he would have been the heavyweight champion of the world. His management blew it but they weren’t thinking about the fighter, they were thinking about the money.”

The buildup, which lasted almost two years, was unsavory. From the start, there was a poisonous injection of racial tension pumped into the promotion. It had been almost 30 years since there had been a dominant white heavyweight champion, Rocky Marciano, and Cooney’s management team, Dennis Rappaport and Mike Jones, milked “The Great White Hope” machine to the full.

Don King, who represented Holmes, only believed in green and if the flamboyant promoter had to mix white and black in the worst way possible to make millions, then he certainly wasn’t going to complain.

Things almost came to a head a year prior to the fight actually taking place. In June 1981, Holmes crushed former heavyweight champion Leon Spinks inside three rounds in Detroit. During the champion’s post-fight interview, with ABC’s Howard Cosell, Cooney made his way over to join the discussion. Holmes reacted angrily, exploding out of his chair to engage in a confrontation and cutting Cosell’s mouth with his elbow in the process.

“It was my interview,” Holmes said, as though stating the obvious. “They came in and tried to take away from what I was doing.

“(Gerry) shouldn’t have bothered me. If (ABC) are going to interview us, then they should say, ‘Hey Larry, we’re going to interview both of you’. Do you know what I’m saying? It was disrespectful and they were taking away from me.”

In November 1981, Holmes survived a shuddering seventh-round knockdown to overcome the unheralded Renaldo Snipes in 11 and the Cooney fight was finally signed.

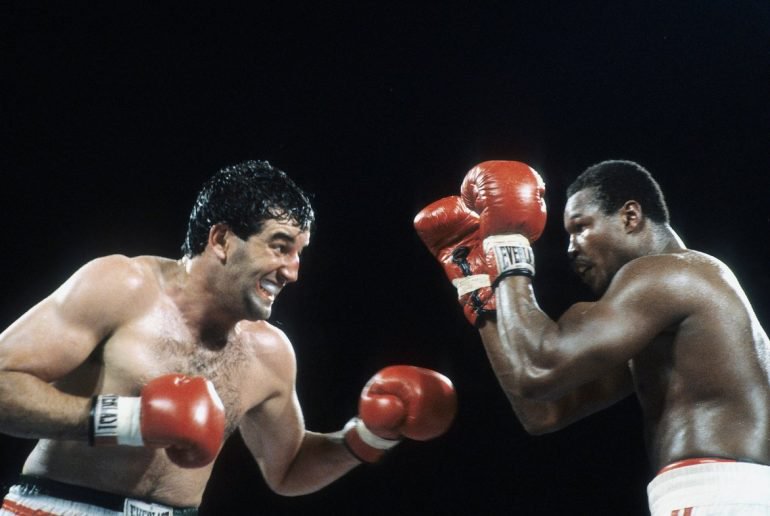

Holmes (right) avoids Cooney’s lethal left hook. Photo by THE RING

The tension between the opposing camps was now at boiling point and hardened boxing insiders had never seen anything like it. In a recent interview with RingTV.com, Barry Tompkins, who called the fight live for HBO, remembered the atmosphere. “That was the most volatile pre-fight I’ve ever been around in my life,” said the Hall-of-Famer. “At the weigh-in, there was a kind of tension in that room that I hadn’t seen before and I haven’t seen since.

“Larry and Gerry were really good guys, who were thrown into a racially charged situation and neither one of them had anything to do with it.”

Perhaps appropriately, the temperature at ringside was a scorching 120 degrees and Holmes continued to be disrespected right up to the opening bell. A telephone line was set up in Cooney’s dressing room, so that President Ronald Reagan could wish him good luck. Holmes was ignored. Then, just prior to the opening bell, Holmes, against all boxing tradition, was introduced first despite being the defending champion.

Still, it was Holmes who drew first blood in the ring when he floored Cooney with a perfect on-two combination in the second round.

“When I hit him with that punch, I was kind of surprised that he went down,” admits Holmes. “Then I tried to take him out but he fought back and was dangerous. So, with me knowing that Cooney was a hard puncher, I didn’t go into fight. I waited until I hurt him again, then I got him.

“It was one of the better fights I fought because I thought about it and tried to figure it out. Gerry was 6-foot 6 and he got long arms and he punches hard. These are the things you had to get around if you want to beat Gerry Cooney. I had to box him and avoid the punches because he was knocking everybody out.”

Holmes absorbed a horrendous low blow in Round 9. Photo by THE RING

Except for a brutal low blow in the ninth, Cooney was unable to really impose his power on Holmes. The vaunted left hook failed to land with full impact. Holmes touched it, parried it, countered it, moved away from it.

Completely exhausted by Round 13, Cooney absorbed a brutal series of head shots, punctuated by a solid right lead. Cooney fell backwards into the ropes and his trainer, the late Victor Valle, entered the ring to rescue his fighter, forcing referee Mills Lane to end the fight. Incredibly, if Cooney hadn’t had three points deducted for low blows, two judges would have had the challenger ahead after 12 rounds.

None of that mattered. Holmes had secured his most emotional and meaningful victory since dethroning Norton in Las Vegas, five years earlier. And surely, with everything he had been through, this victory was sweeter than most?

“No, because I was sad,” countered Holmes. “That was a sad moment for me, not only for me but Gerry had to go through it. I didn’t hate Gerry and that was one of my more difficult times in a fight. I didn’t know Gerry Cooney. All I knew was that he was a guy that fights. A guy that wanted to take my head off. A guy I had to be ready for.

“The blacks wanted me to win and the whites wanted Gerry to win. But I told Gerry, if he wins, he wins. It didn’t have nuthin’ to do with color. Gerry and I are good friends to this day. We talk a lot and we do things together. We talk about (other) people (involved in that promotion) and how they felt and things they said but, you know what, I let that go. I don’t pay that no mind.”

One was a great heavyweight champion and a future Hall of Famer. The other was a dangerous and determined contender, who tried in vain to fulfil a dream. Both made for a terrific prizefight and, everything else being equal, that’s all anyone should have been asking for.

More News

IBF Asia Heavyweight Title Fight: Bisutti vs. Nattapong

Liu Gang, Brico Santig Join Forces

Highland’s Double Impact: August 18 at Lumpinee