His reflexes finely tuned, Montell Griffin had seen the punch coming and was able to react.

The Chicago-based light heavyweight pulled his head back from what he expected to be a left hook but, instead, the shot came roaring upward at approximately 45 degrees. The sudden momentum Roy Jones Jr. had generated by pushing off his back foot had also brought him much closer than Griffin anticipated and the flush half hook-half uppercut floored him heavily. The fight was over in one round.

That was the second chapter in this story, though. This rivalry had begun in earnest five months earlier.

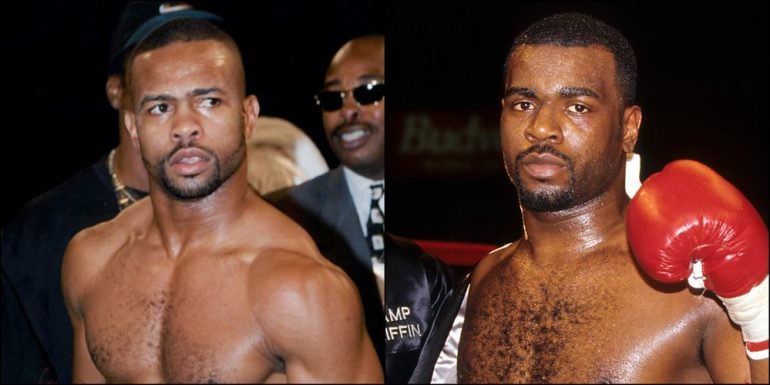

In March 1997, the unbeaten Jones (34-0, 29 knockouts) was the WBC light heavyweight titleholder and Griffin had been selected for his maiden defense, which would be staged at the Taj Majal Hotel and Casino in Atlantic City.

The immensely gifted Jones had begun his professional career as a junior middleweight and claimed titles at 160 and 168 pounds on route to becoming the finest fighter in the world. An Olympic silver medalist at the Seoul Olympics in 1988, his notable pro victories were impressive unanimous decisions over Bernard Hopkins and James Toney. Jones was special.

Griffin had defeated Toney twice, albeit controversially, on his way to amassing a record of 27-0 (18 KOs). A natural 175-pounder, his classy boxing style belied his physical dimensions. Many would expect a 5-foot-7-inch light heavyweight to mix it up like, say, Dwight Muhammad Qawi, but Griffin was a natural counter puncher who worked well off an educated left jab. Like Jones, he was a former Olympian who, despite not winning a medal at Barcelona 1992, possessed an excellent and well-rounded skill set. Griffin had also been developed as a professional by Hall-of-Fame trainer Eddie Futch.

Jones’ mantra heading into the first fight with Griffin was “patience is a virtue.” He planned to make the challenger lead in a bid to counter the counter puncher, but that proved to be easier said than done. Griffin brought plenty of tools to the woodshed and had more success against Jones than any previous opponent. He feinted brilliantly, took away Jones’ left hook by keeping his right hand high and generally gave the champion a nightmare. An unconvincing left-hook knockdown by Jones in the seventh had evened up the scoring but it wouldn’t matter light of what happened in the ninth.

In that round, a lightning-quick right hand rocked Griffin’s world. Jones, sensing urgency, picked up the pace and smashed home a series of accurate power shots. The challenger, realizing that he was about to be knocked out, smartly took a knee. And then it happened. Jones tipped Griffin with a light right hand to the head but followed with a hard left hook. Griffin began to complain to referee Tony Perez before falling on his head.

In that round, a lightning-quick right hand rocked Griffin’s world. Jones, sensing urgency, picked up the pace and smashed home a series of accurate power shots. The challenger, realizing that he was about to be knocked out, smartly took a knee. And then it happened. Jones tipped Griffin with a light right hand to the head but followed with a hard left hook. Griffin began to complain to referee Tony Perez before falling on his head.

The challenger was initially counted out but after consultation with New Jersey State Athletic Commissioner Larry Hazzard, Perez elected to disqualify Jones, who was positively aghast. He had lost his perfect record, lost his WBC title and lost his reputation as boxing’s best pound-for-pound fighter.

Griffin was the new champion but Jones vowed to serve a dish of cold revenge when the pair signed for the rematch, which would take place at the Foxwoods Resort in Mashantucket, Connecticut, on August 7, 1997.

A lot changed in the ensuing five months. Jones trained like a man possessed. Griffin and Futch parted ways over a money dispute. Jones, now the sentimental favorite, vowed to come out blazing. Griffin, who many believed faked his way to a disqualification victory, was public enemy No. 1.

On the night of the rematch, Jones entered the ring in a mock tuxedo — his version of business dress — and looked ready for combat. His physique was solid and he stared daggers at Griffin, who looked pensive. When the bell rang, Jones marched out to ring center and floored Griffin within 20 seconds with a blistering left hook to the jaw. It was all so different from last time.

And then came the half hook, half uppercut. Griffin hit the canvas for the second time in the opening round. His mind was active but his limbs were practically lifeless. Realizing that his body was betraying him for the first time in his professional career, the stricken fighter shook his head in protest. He rolled over onto his stomach, he got to his knees, he fell backward, he fell forward into ringside photographers while they snapped pictures of his ordeal. And when he fell for the final time, the 10-count was completed by referee Arthur Mercante Sr.

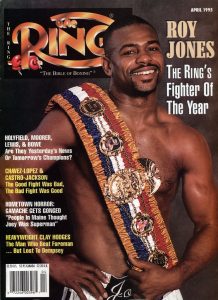

“Jones gets his vindication via a first-round knockout,” bellowed HBO’s Jim Lampley as the victor leaped up on to the ropes of his own corner in celebration. The time was 2:31 and in those 151 seconds, the world had seen Roy Jones Jr. at his very best. He had reclaimed his status as the No. 1 fighter in the world and more world titles, including unification victories at 175 pounds and a WBA version at heavyweight, would be in his future.

Although he hung tough against a variety of top light heavyweights, Griffin never won another version of a world title. His skills and accomplishments are underrated and he deserves credit for a distinguished career.

Ringsiders pay big money for fights involving the best in the world and main events lasting less than three minutes are rarely popular. There are exceptions however. Jones-Griffin II fits into the same category as Joe Louis-Max Schmeling II or Mike Tyson-Michael Spinks. The knockout was so clinical, the ending so decisive, that the result transcended the length of the bout itself.

If you were lucky enough to see Jones that night, then the experience was worth every penny.

More News

IBF Asia Heavyweight Title Fight: Bisutti vs. Nattapong

Liu Gang, Brico Santig Join Forces

Highland’s Double Impact: August 18 at Lumpinee