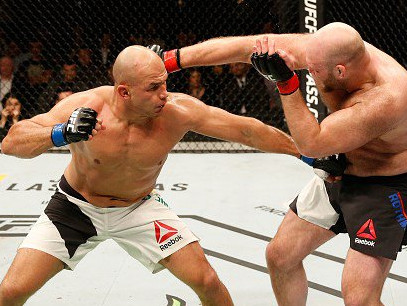

Bloody Elbow’s Connor Ruebusch breaks down the subtle improvements Junior Dos Santos showed in his last fight, and looks at how these new skills might be used to dethrone heavyweight champion Stipe Miocic at UFC 211.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/54708759/usa-today-9243850.0.jpg)

This Saturday, May 13th, Junior Dos Santos will challenge Stipe Miocic’s claim to the UFC heavyweight championship. It has been a long road for the Brazilian, not only since his first fight with Miocic in 2014, but since he won the belt himself in 2011 with a shocking knockout over Cain Velasquez. Since his first title defense, Dos Santos has alternated wins and losses, two of those losses by knockout.

In MMA, it often seems that striking defense is the last skill to develop. For Dos Santos, who has never been an exceptionally diverse defender, this may well be the case. Defense alone, however, has never been Junior’s most pressing problem. He can take punches as well as any man in the heavyweight division, and he can deliver such hellacious counters that even the most confident of foes must think hard before taking a chance and stepping into his range. Cagecraft was the skill that always evaded Junior Dos Santos, just as its absence prevented him from evading his opponents.

As we prepare for this rerun of a classic heavyweight fight, let’s take a look at the fighting style of heavyweight MMA’s most endearing figure, and the limitations that made his worst losses so predictably painful.

WHAT IS CAGECRAFT?

To understand the problems that have plagued Dos Santos for the last half-decade, we have to understand the concept of cagecraft. It’s a nebulous term, and you might stumble upon a dozen different interpretations were you to type the word into a search engine. For our purposes, however, cagecraft refers to the way that a fighter navigates and controls the space of the fighting area, and the pace of the fight within it. Call it cage generalship if you’re feeling fancy.

There are many elements of good cagecraft. Distance management. Efficiency and balance of striking. Footwork, of course. But all of these other factors are secondary to a single, foundational concept: to control the cage, you have to know where you stand in it.

That Dos Santos lacked this awareness was made abundantly clear in his rematch with Cain Velasquez. After a few spirited exchanges, he allowed himself to be backed into the fence. Then Velasquez knocked him down. After that, it was all auto-pilot for the man who had never learned to deal with this kind of pressure. Velasquez won a lopsided decision. When his hand was raised and the belt placed back around his waist, the battered man standing next to him was all but unrecognizable as the former champion.

In the rubber match, Dos Santos was no more difficult to put against the fence. Instead of treating the chain link like hot lava, he seemed to have spent his camp developing a few tricky moves to counter Velasquez from that cornered, compromised position. The sneaky elbows were nifty indeed, but learning to fight Velasquez with your back against the wall is sort of like training nothing but armbar defense in preparation for a fight with Ronda Rousey. Dos Santos wrote for himself a self-fulfilling prophecy, and this time Velasquez knocked him out.

Exchanges like this were the root of the problem.

1. Cain Velasquez, being Cain Velasquez, presses forward.

2. Dos Santos meets his pressure with a jab feint.

3. He follows with a cross to the ribs, and eats a light left hook from Velasquez.

4. Following up, Dos Santos swings for a wide left hook, but Velasquez’s straight right gets there first.

5. Junior misses big . . .

6. . . . and the momentum, aided by Velasquez’s cross, sends him back several feet.

7. As Cain closes, Junior once again trades a right to the body for a left hook on the jaw.

8. And again he follows with a hook. Both fighters miss.

9. But Dos Santos is forced to take another backward step.

10. Velasquez takes a hard step forward.

11. Dos Santos whiffs on a huge right hand as Velasquez changes levels . . .

12. . . . and gets Junior right where he wants him, tied up against the fence.

blah

In truth, Velasquez is simply a terrible style matchup for Dos Santos. Even had Junior fought the perfect fight, Velasquez’s high-pressure combo of wrestling and machine-gun boxing would have been a tall hurdle to overcome. Rather than adjusting to the matchup, however, Dos Santos leaned into it, either accepting the idea that he needed another flash knockout to win, or else totally unaware of the strategy necessary to keep Velasquez from fighting his fight. Perhaps both.

CULTIVATING CAGECRAFT

Following the second loss to Velasquez, Dos Santos struggled to regain his footing, and his place in the division. He impressed by beating Stipe Miocic a year after failing to regain his belt, but the back-and-forth nature of the fight was troubling. Dos Santos relied a great deal on his durability and conditioning, and a new set of bulging muscles had the normally quick fighter looking sluggish. He never managed to gain full control of a surprisingly game Miocic. Wisely taking another year and moving to American Top Team, Dos Santos struggled to find the right balance between cautious defense and all-out aggression when he took on Alistair Overeem, who wanted nothing more than to avoid the gifted puncher’s boxing range. Dos Santos was knocked out for just the second time in his career, and it seemed that his title aspirations evaporated as he crashed to the canvas.

Four months later, however, Dos Santos took on Ben Rothwell, who was riding an impressive four-fight win streak at the time. It was a potentially dangerous matchup for the former champion, and fans wondered whether he would ever be able to recapture his old form. Junior did more than that. Over five rounds, he took Rothwell apart piece by piece, regaining his confidence while also showing tremendous improvements in technique and strategy.

As you might expect, a new grasp of cagecraft was the crown jewel of Dos Santos’ win. The man who had repeatedly found the fence sneaking up on him against Cain Velasquez was now fully aware of his position in the cage, and loathto let himself be trapped against the fence. Over and over, he fought methodically to keep his distance, and put himself back in open space.

Take a look.

1. Ben Rothwell marches forward.

2. Timing his steps, Dos Santos stabs him in the belly with a stiff jab . . .

3. . . . and quickly disengages.

4. Rothwell comes forward aggressively again.

5. Dos Santos times Rothwell’s right hand and, anticipating a slip, throws his own right hand to the chest.

6. Rothwell, throwing his punch wide, finds the mark, but it is more of a light slap than a punch.

7. Junior pulls back, and sees that Rothwell is intent on continuing the attack.

8. He exits with a jab, sticking his left hand in Rothwell’s face as he steps away.

9. And because he circles to the right as he retreats, he gets clear of Rothwell’s follow-up left hook.

10. Dos Santos reclaims the open space.

The difference here is a matter of inches. When Cain Velasquez backed Junior up to the fence, he repeatedly reacted too late, struggling to retreat when the wall was already at his back. Against Rothwell, however, he was eminently aware of his position in the cage. Here, instead of planting his feet and throwing bombs to ward off a determined opponent, he throws single, straight punches, and moves his feet after each one. When he feels the fence creeping up behind him, he uses his jab to enforce the distance while he slips away and circles. The movements are still fairly wide–we will touch on that more extensively in a few moments–but they are executed at the proper time, well before Dos Santos ever feels the cold chain link on his skin.

Even Junior’s offensive tactics were adjusted to suit his defensive strategy. He made extensive use of the body jab, which not only sapped Rothwell’s strength over the course of the fight, but made for a painful obstacle for the pressuring fighter. When Rothwell stepped forward, Dos Santos hit him center-mass, stopping him in his tracks and buying himself a few moments with which to reset. Rothwell was no easily dissuaded, but Dos Santos stuck to his gameplan. When Rothwell surged forward, hoping to overcome Dos Santos’ clever tactics with raw aggression, Dos Santos found opportunities to hurt him with more powerful strikes.

1. Rothwell marches forward, head back and hips forward.

2. Dos Santos takes the easy target, sticking a hard jab into Rothwell’s gut.

3. Circling as he resets, Dos Santos waits on Rothwell to reengage.

4. When he does, Junior stabs him with another body jab just as Rothwell plants his weight on his front foot.

5. And Dos Santos disengages again.

6. Rothwell changes stance, looking to close distance quickly by shifting.

7. Dos Santos retreats in good order . . .

8. . . . and, just as Rothwell squares up in front of him, he throws a quick, long hook . . .

9. . . . followed on the half-beat by a perfectly straight right hand to Rothwell’s nose.

There are two power punches that play very nicely off the body jab. There is the overhand right, which comes from the opposite angle to the body jab, and connects cleanly if the opponent attempts to turn away to protect his torso. Junior, who possesses a crushing right hand, has always been very fond of this set-up. But there is also the left hook. This punch works beautifully when the opponent attempts to parry the body jab, arcing over the top of his hand as he reaches for the body shot that never comes.

In this sequence, Dos Santos uses both together, to brilliant effect. He establishes the body jab, and notes that Rothwell drops his right hand in a latent attempt to swat it away. Up to this point, however, Junior has had trouble landing the hook as anything but a counter, because Rothwell consistently reverts to an awkward, arms-outstretched high guard. In fact, the reason the body shots have been so effective throughout the fight is that Rothwell’s hands are high by default, and he is late every time he attempts to defend. So Dos Santos plays a little trick. He leans forward as if to suggest a jab to the body, then lets the left hook go. As expected, Rothwell gets his glove in front of the hook, and even attempts to counter with a right hand. But the hook was only a throwaway punch: a set-up of a set-up. Junior’s real attack, a thunderbolt of a straight right, smashes into Rothwell’s nose–and he even manages to slip Rothwell’s counter in the process.

So Dos Santos was not merely throwing conventional combinations, relying on the same-old “body-head” logic that had always driven his attacks in the past. He was thinking beyond the rote combo, calculating possible reactions and adjusting his tactics to account for them. In landing this particular right hand, Dos Santos was two full steps ahead of Rothwell, like a chess player in four-ounce gloves.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Dos Santos showed marked improvement against Rothwell, but his evolution is not yet complete. Rothwell had his moments in the fight, landing a handful of thudding blows and, on a few occasions, bull-rushing Dos Santos into the fence.

One of the ways that Dos Santos might have avoided this was by closing the distance himself. Sticking to an out-fighting strategy, Junior was determined to keep a wide gap between himself and Rothwell at all times. At the elite level, however, this will never be possible. Men like Ben Rothwell and Stipe Miocic can take a few punches on the way in. Men like Cain Velasquez are sharp enough to evade those punches even as they step forward. When a top fighter is determined to close the gap, no matter how sharp your jab or how perfect your footwork, eventually he will put you in a corner.

The solution is to close the gap on your own terms. If the opponent wants to pressure, and you are on the verge of being backed into the fence, you can give him a shock by bending your knees and stepping into him. Top out-fighters in boxing do this all the time, and while the fact that MMA does not end in the clinch complicates this tactic for men like Junior Dos Santos, the logic remains sound. In fact, Dos Santos is a good enough wrestler to clinch with anybody in the heavyweight division, especially if he is the one who initiates the clinch. By stepping forward and grabbing underhooks as Rothwell prepared to charge, Dos Santos could have spun Rothwell into the fence and disengaged with little difficulty.

Though he did not do this against Rothwell, Dos Santos nonetheless made it clear that such a tactic would have worked. For example, take a look at this exchange of right hands.

1. Dos Santos tries to misdirect Rothwell with lateral movement, stepping first to his right . . .

2. . . . and then to his left. Rothwell changes stance to keep Dos Santos in his sights.

3. Rothwell shifts, moving forward in a wide stance to prevent Dos Santos from evading him.

4. Instead of evading, Junior drops his weight . . .

5. . . . and throws a looping right hand. Rothwell slips while throwing an overhand of his own, and both punches miss.

6. Having closed the distance, however, Dos Santos quickly crossfaces Rothwell . . .

7. . . . and turns him with the aid of a short underhook.

8. Rothwell tumbles, and Dos Santos finds himself once again in the center of the Octagon.

Though this brief clinch exchange is more or less accidental, Dos Santos proves the effectiveness of closing distance before his foe can do it first. Because he initiates the attack as Rothwell comes forward, he manages to recover his balance while Rothwell is still following through on his punch. That means he gets to make the first move on the inside, and Junior demonstrates that his clinch wrestling is more than good enough to off-balance Rothwell and regain the center of the cage.

The rule of thumb for out-fighters is this: all the way out, or all the way in. Dos Santos has already proven that he can master the first range when given the chance, but Stipe Miocic will look for every opportunity to engage in the pocket and tie Junior up against the fence. In order to fight from his preferred long range, Dos Santos would be well-advised to force the tie-ups on his own terms. Take away space first in order to create it later.

What’s more, when Dos Santos did find himself backed into the fence, a few of his bad habits cropped up again. Nearly every time Rothwell crashed toward him with a combination, Junior sought to escape like this:

This position is not all bad. Dos Santos has his chin tucked behind his shoulder and his head off-line. He is moving laterally along the fence rather than standing straight up against it. That’s all good stuff.

The problem is that this position is purely defensive. Junior is facing away from Rothwell, all but turning his back on his opponent as he attempts to jog out of harm’s way. They say that the best defense is a good offense, and while we have already exposed the folly of trying to meet every attack with force, it is true that the threat of offense is always helpful. This position, brief though it is, is not just defensive in intention, but in appearance as well. Dos Santos doesn’t look ready to launch any kind of attack as he abandons his stance and turns to the side, because he isn’t.

For a demonstration of how Dos Santos might have retreated, let’s look at Lionel Rose, decked out her in green and white as he masterfully outmaneuvers the legendary Fighting Harada.

Take note of how Rose positions himself as he evades Harada’s attacks. His left foot is always pointed directly at the center of Harada’s body, presenting a threat to the pressuring fighter. The jab which lines up with that foot makes the threat real. Wherever Rose’s feet are pointed, his left hand is ready to snap out and punish Harada for daring to attack. Over and over, he snaps off that sharp jab and moves his feet, never giving up control of the center line.

If Dos Santos continues to improve on the developments he showed against Rothwell, this sort of airtight positioning will be evidence that he is making the right steps. If he combines that positioning with a few well-timed steps into the clinch, he should be able to outdo his first win over Stipe Miocic, and regain his belt.

–

For more on the scintillating matchup between Dos Santos and Stipe Miocic, check out the latest episode of Heavy Hands, the only podcast dedicated to the finer points of face-punching.

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8479833/1.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8492835/3.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8492841/4.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8492855/2.0.png)

/cdn0.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/8492827/5.0.png)

More News

UFC269: Venezuelan Julianna Peña Submits Brazilian Amanda Nunes, Becomes the new UFC World Champion

Oliveira, Poitier Make Weight for UFC World Title

Hot UFC269: this Saturday Oliveira vs Poirier Ready for War in Las Vegas