Not long ago, I read this fascinating New York Times piece on the boxing writer, Brin-Jonathan Butler. The author, Alex Vadukul, refers to Butler as “among his generation’s foremost boxing writers,” and I agree. I had read some of Butler’s work online, and I was already a fan. Reading the Times piece, though, and learning about his time spent training in Cuba, his fling with one of Fidel Castro’s granddaughters, and his encounter with the real life protagonist behind Hemingway’s The Old Man and the Sea, I thought, I really have to meet this guy.

An email later, and the next night I found myself with Butler at a Cuban bar in Spanish Harlem, where we talked for nearly four hours over cocktails. As I suspected would be true, not only did Butler turn out to be engaging and kind, he also proved to be a world class storyteller and a tireless fount of anecdotes and ruminations about boxing. He is the kind of guy you want to keep drinking and talking as long as you can, and as the night unwound, our conversation ranged from Mike Tyson, to the Cuban amateurs, to the occasional boxing writer Joyce Carol Oates (he’s not a fan), to our favorite writers and poets, and beyond.

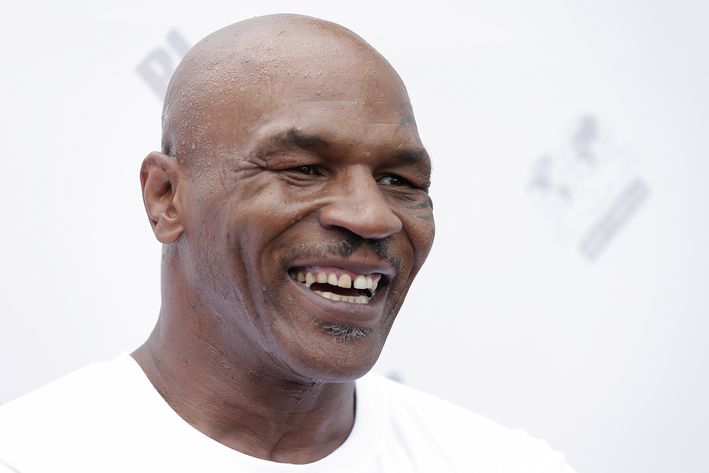

It’s too much for one interview, and the thought of transcribing it all at once is daunting. It would be easier to present it as an audio interview, but this was not a quiet bar. So I’m transcribing our conversation in sections, and I’m going to be sharing them here at Bad Left Hook. This first installment details Butler’s thoughts on Mike Tyson, who he interviewed recently. A lot of people have said a lot of things about Iron Mike, but Butler goes further and provides a portrait of Tyson that is as compelling as it is dark.

You’re going to want to read this. Then you’re going to want to read his amazing book on Cuban boxing and its culture, The Domino Diaries. He also has a forthcoming documentary, Split-Decision, which contains interviews with Felix Savon and Guillermo Rigondeaux, as well as the last known interview with Teofilo Stevenson before he died in 2012.

Interview with Brin-Jonathan Butler, Part I, Mike Tyson

Me: So you were the first one to ask Mike Tyson if he had ever been abused as a kid?

Butler: Yes. In my Amazon Kindle Single interview with him I was the first person to broach that issue. Certainly not to expose him, but to understand him. Mike Tyson first came on my radar when he talked about his history with being bullied. That’s what drew me to him long before I was a fan of anything he did in the ring. I was shocked at how articulately he described torment and humiliation of bullying and to have it come from the so-called “baddest man on the planet” blew me away about his complexity and depth as a human being and character in our society. He wrote in his memoir that he had been abducted on the street and that someone had taken advantage of him and attempted to sexually assault him. He never returned to that point again in the book and he’d never mentioned it ever before. When I got to interview him, it was a year after it had been published. Nobody picked up on it. He agreed to meet with me at the Ritz Carleton in Battery Park.

I started thinking about a common thread in so many of the statements he had made, the controversial and offensive statements that he made. Mike Tyson is arguably the most scrutinized celebrity the world has ever had. Yet he has always maintained the power to surprise us. His self-awareness, I think, is far beyond the awareness we possess as a culture about ourselves. He’s exploited that disparity throughout his career marketing himself to us. He even says that, “All my best quotes sound like I’m quoting somebody.” It’s performance. Theater. We wanted Jaws? We wanted, to quote Scarface, “the bad guy?” He gave us that. But some of those quotes he’s most famous for hid perhaps the darkest thing he ever confronted in plain sight: this history he’d had with being sexually molested as a child.

Me: So you think he is quoting a part of himself that he walled off?

Butler: Or something somebody said to him. During the Lennox Lewis fight lead up he said, “I’ll fuck you till you love me faggot.” Think about that emotional construct for a second. It’s chilling. I’ll victimize and violate you until you love me. My hunch was, nobody would understand that more than the victim of that terrible, unspeakable aggression. For someone who spent as much time in prison as he has–especially as a child, let’s remember–had anyone ever asked him if he had been sexually assaulted? No, never. Where he is constantly saying to Razor Ruddick, “I want to kiss those big lips of yours.” He loved homoerotic taunts and playing with that theater for a mainstream audience. And this was a guy who, as a teenager, frequently kissed the lips of his trainer on the mouth.

Me: Yeah, you know it went beyond that old school way boxers show affection to one another, a little more.

Butler: It certainly caught a lot of people’s attention that he showed such tenderness in a very homophobic culture on the one hand and then this incredibly menacing, predatory, sexually-charged attitude toward some of his opponents at other times. You get the impression that there is something unmentioned that is scary, really scary, he’s confronting or being confronted with that he’s never escaped. And then he offers this little crack in the door by acknowledging it in that memoir. Almost like a tease. So I thought it was weird that no one was taking him up on it. So I waited until about halfway though our interview and asked him. I had asked some other people who knew him if they had ever thought of this issue in relation to Tyson. They said sure. So I asked why they never mentioned it and they said, “Do you want to be the first person to ask Mike Tyson this and have it go wrong?”

Me: haha! Yes, I can see their point.

Butler: When I asked him point blank about it there was a pause and he said, “yes.” I said, “was it the only time?” There was another pause that seemed very pregnant, and then he said, “it was the only time.” It was a strange moment. He also made clear he left out many of the darkest things from his life in that memoir. But it was as far as he wanted to go discussing this one issue. I don’t know that he was abused multiple times, but that was my intuition while he was saying that. The issue felt suffocating in the room long after he’d turned the page and wanted to discuss other things. And then, in a move that totally fascinated me, the next day he goes on a major radio show and, unprompted, raised the issue of being a victim of sexual assault. He went public. So what were the inner mechanics of my raising it the day before and him putting it out there on his own? I really don’t have that answer.

Me: You triggered something.

Butler: It was very much on his mind.

Me: You got under his skin a little bit.

Butler: I wonder if he saw the value in terms of humanizing him to the public with finally letting it out there. The host who he was discussing that issue with followed up, and the response to one of his questions was, “I know that this affected me, but I just don’t know how.” I thought that kind of nebulous response to all this is just so honest and so consistent with other victims of that issue I’ve known and talked to over the years. But then you look at the way he used this darkness to sell his fights. Again, I marvel at someone who has been dissected like very few human beings have ever endured in the media and again and again and again, he shocks us.

Me: That’s amazing. It makes me think of something you wrote elsewhere, that you got into boxing for the same reason that everyone gets into boxing, to restore lost pride.

Butler. Respect. To restore self-respect. To heal and feel safe in the world. The popular narrative is boxers are very violent people who repress it outside of the ring. I think it’s the opposite. Boxers have learned who they are through violence and gotten very close to that horrifying fire most people would give anything to avoid. It’s made most of the boxers I’ve met in the sport some of the gentlest people to be around. They have nothing to prove because they know who they are in a way very few men do.

Me: Gotcha. Then I think about your Tyson story and try to put those things together. The lost respect from this abuse that he experienced is translated into this kind of dark perpetuation of the sexual crime, sublimating it into in-ring violence. So it’s reclaiming lost respect in a way, but it’s also inflicting his abuse on others. He’s threatening to fuck others in the ring. I mean, not literally. It’s like he’s turning the ring experience into something borderline homoerotic…

Butler: Right.

Me: Not that this is normal…

Butler: Even Desiree Washington testified at his rape trial that when he began to rape her … you know, the crime for which he was convicted, what he said was “Don’t fight me mommy.”

Me: Wow…

Butler: So if it’s not one dark sexual thing, it’s something equally dark from this guy. So my thing with Tyson is. You think, he’s the monster, he’s this scary guy. He’s tremendously successful. His act took home more money than anybody’s in film, music, sports--21 million for 91 seconds against Spinks in 1988? Twenty-five million in 1995 fighting Peter McNeeley? We turned him into the most lucrative spectacle in America at the time. A commodity’s value is based on desire. Which is where, unfortunately, we come in. What does that say about us?

America is a country where before Jesse James was shot in the back of the head by Robert Ford, he had a more famous face than the president. Francis Ford Coppola couldn’t believe that The Godfather had audiences cheering for Michael Corleone after selling his soul for power. Wall Street wasn’t intended to have Americans cheer on Gordon Gekko. But we love the villain. We’ve become or have always been a bit like Jimmy in Goodfellas, rooting for the bad guy in movies. Tyson wasn’t always playing the villain. But I think he correctly understood we’d pay more for a villain than we would a hero. And he was certainly proved right. In a culture that has as notoriously short of an attention span as ours, this guy’s held our attention, riveted our attention, going on three decades.

Mayweather and Al Haymon tweaked Money Mayweather’s character from Tyson’s second act in the ring. The tweak was that since nobody had ever paid much to watch Mayweather win, he’d become so obnoxious as “Money” we’d pay anything for the pleasure of watching him lose. But we didn’t tune in to watch Tyson lose. We weren’t even necessarily paying to watch him win. We just wanted to spend time with him [laughing]. Almost all of Mayweather’s fights left his customers feeling cheated. That wasn’t the case with Tyson. That identification with someone like what Tyson presented us always fascinated me on a sociological level. It’s way bigger than sports.

Me: That’s so interesting. I always attributed his phenomenal popularity to the way his style convinces us that he is some kind of primal act of nature.

Butler: That’s how we comforted ourselves and justified our fascination. But remember, horror films, as a genre, are built on the premise of an audience enjoying the suffering of those on screen. I always found what Tyson’s marketing brilliance exposed about us a lot scarier than anything it exposed about him.

Me: I guess I got stuck in that. Maybe I am just reading into it what I thought I liked about watching Tyson. But listening to what you say about how he was diagnosing us, even as we were trying to size him up … he was adjusting to us, to our evolving perceptions of who he was.

Butler: When you consider that he basically gave up on boxing after Spinks in 1988 and not only never improved but slid pretty precipitously after that–and he fought until 2005–we never got bored. I’ve never met anybody who was more desperate to be loved than Tyson. And, like a lot of kids who grew up without being loved, they’ll make damn sure they’ll at least give you something to look at.

More News

Marcial vs Sinam in Manila

Era, Lukas, Innes Win in Thailand

Vitor vs Kim in Bohol